|

Chapter

Eleven The Emergence Of Diversity: Women, District Representation Dr. Dan L. Morrill University of North Carolina at Charlotte E-mail comments to N4JFJ@aol.com

The thirty years following the end of World War Two in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County were anything but dull and boring. These three decades are rivaled in importance in terms of fundamental social and political modification only by the arrival of white settlers in the 1740s, the defeat of the Confederacy and the end of slavery in the 1860s, and the overpowering of Populism and the enactment of Jim Crow laws at the turn of the last century. Change occurred on many fronts, but all shared the common result of increasing participation by a broader spectrum of society in influencing and making decisions about the future of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. The decades immediately following World War II also witnessed a major shift in the architecture of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. Modernist architects, including A. G. Odell, Jr., J. N. Pease, Jr., rose to prominence in Charlotte during these years and became outspoken advocates of principles of design that rejected traditional notions of beauty, especially the attachment of decorative ornamentation to the outsides of buildings. Infused with optimistic expectations of the future, architects like Odell and Pease argued that buildings should encourage humanity to move boldly into a bright, prosperous, and better "world of tomorrow." "The basic tenets of Modernism emphasized function and utility; abstract beauty, sculptural form, and symbolism; honesty in materials, and the use of modern materials and technology as well as an emphasis on the use of natural materials," write historians Sherry Joines Wyatt and Sarah Woodard. A. G. Odell, Jr. had nothing but disdain for the architecture he observed when he arrived in Charlotte in the late 1930s. "There was nothing here," he remembered, "that illustrated the honesty of stone as stone, steel as steel, glass as glass. Everybody was still wallowing in the Colonial heritage." Odell, Pease, and other Charlotte architects were determined to change that circumstance. Nobody was predicting profound change when World War Two came to an end. Everybody assumed that it would be "business as usual." Indeed, during the immediate post-war years it looked as if Charlotte’s white male business elite would continue to monopolize local power. The process by which Independence Boulevard came into being seemed to affirm this truth. Independence Boulevard tore this community apart. Beneath the deafening din of car horns and truck exhausts one can still hear the anguished cries of the hundreds of Chantilly , Elizabeth , and Piedmont Park residents who gathered at Midwood School on Central Avenue on September 8, 1946. These were desperate people who had just learned that Mayor Herbert Baxter and the City Council wanted to use $200,000 of local bond money to help build a massive "cross-town boulevard" up Westmoreland Avenue, down High Street, and across the Sunnyside Rose Garden, through Independence Park , along Fox Street past the Douglas and Sing Mortuary, through Cherry and the Thompson Orphanage pasture, up Stonewall Street and down Brevard Street to end at Morehead Street.

The protestors called it a "foolish scheme" that could "throttle traffic between downtown and the eastern residential districts." One irate resident suggested that the route had been chosen because it would increase the value of the property that Ben Douglas , District Highway Commissioner and former Mayor, owned at what is now the intersection of Independence Boulevard and Elizabeth Avenue. "In fact, it is strange," the irate citizen proclaimed, "how the highway seems to seek out the schools, the stadium, one of the few parks we have, the Rose Garden and other such places to bring its roaring buses and streams of cars along throughout the day and night." "Virtually everybody who lives in the eastern part of the city will have to cross its snake-like meandering," the group warned. Lucille K. Tyson , an elderly lady, lived at 829 South Brevard Street, right in the path of the proposed "cross-town boulevard." "My thoughts may not mean so much, but I feel pretty blue and washed up today," she lamented in a letter to the Charlotte Observer on March 13, 1947. "Many times I've looked out to see surveyors all around the place, our property staked off. Again, an official sitting in a parked car observing and figuring." Ms. Tyson felt powerless, maybe afraid, as she saw her whole world crashing down around her and saw no way out of her dilemma. "We work and work to enjoy a few happy moments in our old years, knowing we do not have many more to go. Here comes a new idea. A Super Highway! There! We have to pick up and go," she decried. "Certainly, I feel let down about having to lose a home. It is something to think about when it hits you."

"Somebody's toes are bound to be stepped on." That's how Councilman John P. White , the affable, cigar-smoking, 67-year-old production manager and mechanical superintendent of the Charlotte Observer responded to the protestors of the proposed "cross-town boulevard." A native of Alabama, White lived on Grandin Road in the Wesley Heights neighborhood off West Trade Street. Like the majority of Charlotte businessmen of that era, he was caught up in the euphoria and optimism that gripped the country in the years immediately after World War Two. Exciting things were happening all over Charlotte. The real estate market was booming, as developers like C. D. Spangler Sr . and John Crosland labored feverishly to provide housing for the hordes of veterans who were marrying and beginning their families. Brides appeared in regal, white gowns on page after page of the Sunday newspaper, serenely ready to partake of the wonders of the newest kitchen paraphernalia. Dishwashers. Electric can openers. WBT was about to put its FM station on the air. Bing Crosby and Ingrid Bergman were starring in "The Bells of St. Mary's" at the Carolina Theater. In August 1946, Liggett Drugstore opened its lavish, modernistic retail outlet on the northeastern corner of the Square, where the Bank of America headquarters is now located. This was not a time for sentimentality or restraint. "You only look back for reasons to move ahead, and by golly nobody can say that we lacked ideas," Mayor Baxter told journalist Kays Gary in 1964. A handsome and personable Bostonian, Herbert Baxter had come to Charlotte during World War One to train at Camp Greene , had settled here, had prospered in the lumber business, and had moved to a fine home on Queens Road in Myers Park . "Because he was so much a doer by nature," the Charlotte Observer reported, "he was never a precise planner, never a man to wait to weigh every possible detail that might go wrong." The same could have been said about Edward Dilworth Latta , Z. V. Taylor , or most of Charlotte’s New South leaders. The real brain behind the building of Independence Boulevard was James B. Marshall . Marshall Park in Uptown Charlotte is named for him. He was a brilliant engineer who had served as Mayor Ben Douglas 's City Manager. Born in Anderson, South Carolina in the early 1890s, Marshall graduated from the College of Charleston and settled in Charlotte in the 1920s. He left City government in 1941 and joined J. N. Pease as an engineer and contact man with City Hall. In 1946, the Charlotte Planning Board hired Marshall as a consultant to prepare a master plan for Charlotte's streets. Several month earlier, the North Carolina Highway Department had conducted a comprehensive survey of local traffic trends and had determined that Charlotte needed "cross-town boulevards" to relieve congestion on uptown streets. The prospect of grand and majestic expressways was music to the ears of men like Mayor Baxter and District Highway Commissioner Douglas. They knew that Charlotte had become a major trucking and distribution center in the first half of the twentieth century and that highways were essential to the local economy. Buildings such as the Charlotte Supply Company Building and the Textile Mill Supply Company Building attested to Charlotte's service to the regional textile industry. The first mention of what was to become Independence Boulevard occurred in the Charlotte Observer on May 7, 1946. C. W. Gilchrist, Chairman of the City Planning Board, announced that Jim Marshall had completed a street plan that included an expressway from Graham Street eastward along Stonewall to Sugar Creek, where it forked, one arm leading to the Monroe and Albemarle highways, and another connecting with Queens Road. On June 4th, City Council adopted Marshall's master scheme, even though the exact route of the cross-town boulevard was still undecided. The issue did not surface again until September 1946, when word leaked out that the expressway would split the Chantilly , Elizabeth , and Piedmont Park neighborhoods. A throng of infuriated citizens packed the City Council meeting on September 10th, and their spokesman, attorney Frank K. Sims, Jr ., accused the City of being secretive and manipulative. They had good reason to be mad. The group had not even seen a map of the proposed route. Mayor Baxter assured the neighborhood leaders that the location of the expressway was still up in the air; he directed City Manager Henry A. Yancey to release maps of the cross-town boulevard; and he promised the protestors that they would have ample time to express their concerns. On October 8, 1946, the City Council gathered for an informal dinner at the Myers Park County Club, where Mayor Baxter was president. In those days it was customary for the Councilmen to decide issues in private and then to emerge like the College of Cardinals and cast their pre-determined votes. Imagine what the scene must have been like. There in the midst of Myers Park, with fine china, cut crystal, and sumptuous food on the table, the representatives of the people endorsed the route through Chantilly , Elizabeth , and Piedmont Park . That's how deals were struck in those days. Baxter and his colleague were following a well-traveled path -- no pun intended. On October 21, 1946, the outraged residents of the affected neighborhoods descended upon City Hall for a public hearing. The atmosphere was tense and electric. "Isn't it a little absurd," Frank Sims remarked, "to build a highway that winds and twists and turns across a park and baseball diamond and over a rose garden and through a thickly populated residential section just to reach Ben Douglas 's property?" Mayor Baxter and the Councilmen did modify their position in the face of this fierce public opposition, at least in terms of the preferred route. They instructed Jim Marshall and Henry Yancey to come up with alternative routes for the expressway. At 2:00 p.m. on November 12, 1946, the City Council toured eastern Charlotte to examine three prospective rights-of-way. One was the original route up Westmoreland Avenue and through Independence Park , from which the cross-town boulevard eventually took its name. A second used Westmoreland but turned left on Hawthorne Lane to Fourth Street and continued across Sugar Creek to Stonewall. The third spared Chantilly , Elizabeth , Piedmont Park , the Sunnyside Rose Garden, and Independence Park by entering the city along Monroe Road, swinging left past the railroad overpass to connect with Randolph Road, continuing to the intersection of Queens Road and Fourth Street, then moving through the Cherry neighborhood to Morehead Street, and proceeding along Morehead to South Boulevard. City Council approved the third route by a vote of 5 to 1 on November 25, 1946. Ponder what that decision would have meant for the Eastover and Crescent Heights neighborhoods and the Mint Museum of Art . But this route was never built, because the Federal government, the principal financier of the project, rejected it outright as unsuitable for an expressway. On December 5, 1946, the Councilmen took up the issue again. For a while it looked like Charlotte would never decide the issue of where to build Independence Boulevard . The members of City Council seemed to be hopelessly divided, two favoring the original route, two supporting Hawthorne Lane, and two opposing the road regardless of its route. City Councilman John P. White saved the day. He persuaded Ross Puette and Henry Newson to abandon Hawthorne Lane and back the original route. "By jingo, at one point there, I thought I was going to have to switch to Hawthorne Lane myself," White laughed. Such were the fickle ways of politics in those days. The battle was not over. City Council approved the contract with the Federal government on March 11, 1947, but the opponents threatened to sue the City for misuse of local bond money. The next City Council had to reaffirm its support for the project in June 1947. The momentum to build the cross-town boulevard was irreversible. And we all live with the consequences -- good and bad.

Few Charlotteans noticed when Bonnie E. Cone , a mathematics teacher at Central High School , was named the director of the Charlotte Center of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1947. The school was a temporary facility created to educate veterans. Cone's appointment to head the institution turned out to be a momentous event and a harbinger of significant change. A woman of indomitable will and determination, Cone began almost immediately laying plans to make the school a permanent institution of higher education. "It is doubtful that city leaders fully anticipated at the beginning the ramifications of having a major university in their midst," writes Ken Sanford in his history of Charlotte College and UNCC . "However," Sanford continues, "the coming of state-supported higher education to Charlotte set in motion a sequence of events that would forever change Charlotte and its greater region."

The creation of Charlotte College in 1949 as a municipal-financed institution and its eventual transformation into the University of North Carolina at Charlotte in 1965 was a seminal development in the history of this community, perhaps as notable as the arrival of Alexander Craighead in 1758, the coming of the first railroad to town in 1852, and the opening of the Charlotte Cotton Mills in 1881. So profound was the impact of Cone's attainments that one must place her accomplishments even above those of Jane Smedburg Wilkes, in this writer's opinion the second most important woman in Charlotte-Mecklenburg history. "Charlotte College wouldn't be where it is now if it hadn't been for her," said Board chairperson J. Murrey Atkins about Bonnie Cone . Bonnie Ethel Cone was born on June 22, 1907, in Lodge, South Carolina, a tiny railroad town of some 200 people located roughly midway between Columbia and Charleston. Reared in a conservative Baptist home, Cone acquired a love of teaching as a young child. Her first students were the animals on her father's farm. "I taught every little animal around in those fantastic years," she told a reporter many years later. "I knew from the time I started to school that I wanted to be a teacher." Always an excellent student, Cone graduated from Coker College, a private liberal arts college in Hartsville, South Carolina, in 1928 with a B.S. in mathematics. She taught in the public schools of South Carolina until 1940. Bonnie Cone earned an M.A. in mathematics from Duke University and moved to Charlotte in 1941 to teach the same subject at Central High School . The school's principal, Dr. Elmer H. Garinger , was most impressed with Cone's intelligence and instructional abilities. In 1943, Cone returned to Duke to work as a statistician for a U.S. Naval Ordnance Laboratory. After a brief stint in Washington, D.C., she returned to Central High School in 1946 and resumed her career as a high school mathematics instructor. Not surprisingly, Elmer Garinger recruited Bonnie Cone also to be a part-time teacher in the newly-opened Charlotte Center of the University of North Carolina. She taught mathematics to engineering students. In August 1947, Garinger summoned Cone to his office and asked her to become the Director of the Charlotte Center, because the first occupant of that position had returned to Chapel Hill. "I took the job of director only as a temporary position," she explained. "I had prepared myself for high school teaching, and that's what I wanted to do." Cone's administrative office was formerly the Lost and Found Room at Central High School . Cone did not own an automobile. She rode a bus to campus from a house where she rented a single room. She had no administrative experience beyond the classroom or what she might have acquired working for the Navy.

Everybody assumed that Cone had taken a dead-end job. Indeed, it is unlikely that Chapel Hill would have allowed a woman to assume the position if the job had appeared to have had any prospects of becoming permanent. "People told me I was out on a limb, that I couldn't last. They said I should look for another job." Cone worked up to eighteen hours a day. She taught classes. She recruited faculty. She even made sure the classrooms were left clean for the high school students who would return the next morning. "I can't say anything but good about her," proclaimed Mary Denny , a long-time associate. Cone's most enjoyable task was advising students. "Miss Cone is one of the very choice people in college education work because she takes such a personal interest in all of the students," said Elmer Garinger . Cone decided to fight to keep the Charlotte Center open because of the educational opportunities the institution provided for students who otherwise would have had little hope of attending college. "I saw what was happening to the young people," she explained. Governor James Holshouser summed up Cone's achievements best at the time of her retirement. "Some people devote their lives to building monuments to themselves. She has devoted hers to building educational opportunities for others." Cone's first major victory came in 1949. She and her supporters won permission from the North Carolina General Assembly to continue the two-year college under the auspices of the Charlotte public school system of which Garinger had just become Superintendent. Named Charlotte College , the institution ran on a shoestring. It operated with part-time faculty in part-time classrooms and had to depend almost solely upon student tuitions for its financial survival. The man responsible for obtaining initial State funding in 1955 for Charlotte College and maybe as influential as Bonnie Cone in the early history of the institution was W. A. Kennedy , nicknamed "Woody." Ken Sanford calls Kennedy the "spiritual father of Charlotte College." Because he died in 1958 and therefore like Moses on Mount Nebo could only look into the "promised land" of the college's present suburban campus, "Woody" Kennedy is largely forgotten. A graduate of North Carolina State University and seller of textile machinery, Kennedy was unswerving in his determination to establish a State-supported institution of higher education in Charlotte. Kennedy worked tirelessly, even spending his own money to prepare and mail out questionnaires to potential backers of the school. Kennedy left no stone unturned in his search for money. If necessary, he and Bonnie Cone would let it be a private institution. At one point he approached Governor Cameron Morrison about giving money to the school, which would then be renamed "Morrison College." Morrison declined. Sometimes Kennedy's rhetoric in support of a State-supported four-year college for Charlotte became strident. "For years Carolina and State have both tried to throw us a sop or bone here in Charlotte in the nature of an extension course in order to keep us quiet," he stated. According to Kennedy, extension courses were not sufficient to meet the educational needs of Charlotte and its environs. "1000 additional high school graduates would go to college each year if they had the same opportunity or the same available facilities as some other areas of the state," Kennedy declared. Characterizing his critics as the same kind of nay Sayers who had told leaders like the Oates Brothers and D. A. Tompkins that Charlotte would never become a major textile center, Kennedy called for a positive attitude on the subject of making Charlotte College a four-year, State-supported institution. "Do you believe in a timid or bold approach to this problem?," he asked. Except for the tenacity of Kennedy and Bonne Cone, Charlotte College would never have moved beyond being a two-year community college. "Miss Cone has provided the faith on which the college many times found its primary ability to exist," commented J. Murrey Atkins . "She has stuck with it and never even thought of giving up when sometimes the sledding seemed pretty hard." Support among the business executives of Charlotte for the school was lukewarm at best. One influential graduate of North Carolina State feared that putting a state-supported college in Charlotte would harm his beloved alma mater. "I would not be in favor of anything that would in any way hinder the growth and prestige of 'dear old State,'" he wrote. The writer was not alone in harboring such sentiments. "Charlotte has never been short on pride," said the Charlotte News on May 11, 1956, "but with the chips down, it has often exhibited distressingly little interest in higher education in the past." Dramatic breakthroughs for Charlotte College did occur in 1957 and 1958. The school began holding its first day classes; it acquired an independent Board of Trustees; local property tax revenues in support of the school increased; and Charlotte College secured options on land for its own campus. Several sites were considered, including the Cameron Morrison Estate or Morrocroft, the former Naval Ammunition Depot site in what is now the Arrowood Industrial Park, a cleared site in the Second Ward or Brooklyn neighborhood, and a 248-acre tract on Highway 49 northeast of Charlotte owned by Construction Brick and Tile Company. On August 12, 1957, the Charlotte College Board of Trustees voted to buy the Highway 49 property. Businessman Oliver Rowe remembered going to the site with Bonnie Cone when the only buildings on the land were a barn and a silo left from earlier farming days. "She reached down and grasped a handful of earth, let it sift through her fingers and said, 'This is the place. This is the place.'"

Charlotte College moved to its suburban campus in 1961. The first two buildings, one named for "Woody" Kennedy, were designed by A. G. Odell, Jr ., the same man David Ovens had selected to design Ovens Auditorium and the Charlotte Coliseum on Independence Boulevard . Odell, the son of a wealthy Concord textile family and graduate of Cornell University, was Charlotte's best known and most prolific Modernist architect. Upset that the Charlotte College buildings resembled those that Odell was designing for St. Andrews College at Laurinburg, Cone nonetheless pushed ahead with Odell's plans for the new campus. A groundbreaking ceremony was held on November 21, 1960, and classes opened the following September. On May 8, 1962, the Board of Trustees voted to request the addition of the junior year in 1963 and the senior year in 1964. The North Carolina General Assembly did approve four-year, state-supported status for Charlotte College in 1963.

Bonnie Cone was seemingly omnipresent on the Charlotte College Campus in those early days. This writer, a brash twenty-five year old historian at the time, joined the faculty in June 1963 and had his first office in what had been the kitchen for the college soda shop. The floor sloped down to a drain in the middle of the room where countless fluids of countless types had once descended into the unknown depths below. Bonnie Cone walked by one day and saw the less than ideal environment in which this writer worked. It might have reminded her of the Lost and Found Room at Central High School . "I will not have a faculty member of mine sit in a place like this," she proclaimed. Carpenters arrived within an hour to rectify the situation. Uppermost in Cone's mind was making Charlotte College a campus of the University of North Carolina system. "Few of the faculty and staff recruited in 1963 and 1964 would have come to the brand new four-year college without seeing through Cone's eyes the university that was to unfold," says Ken Sanford. J. Murrey Atkins , long-time chairman of the Charlotte College Board of Trustees, would not live to see the dream's fulfillment. He died on December 2, 1963. But Bonnie Cone persevered. Victory came on March 2, 1965, when the General Assembly approved the transformation of Charlotte College into the University of North Carolina at Charlotte , effective July 1, 1965. Not since Stephen Mattoon had raised the money to build Biddle Hall in 1883 had Charlotte witnessed such an astounding success in the arena of higher education. A spontaneous celebration erupted on campus when word reached Charlotte from Raleigh. "Miss Cone, can you hear the victory bell ringing?," exclaimed her secretary into the telephone. Certainly, there were influential women in this community before Bonnie Cone . Not the least among them was Gladys Avery Tillett . Tillett labored tirelessly for the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, even using a handkerchief embroidered "Votes for Women." She helped found the Mecklenburg League of Women Voters and was an active Democrat until her death in 1984. It was in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s that substantial numbers of women began to assume positions of political influence in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. "A lot of women became involved in the political process in our community -- not just pouring the tea and helping the guys, but getting out there themselves and being in the forefront," remembered one member of the Women's Political Caucus. "It was very exciting, the beginning of women feeling they had some power, to be reckoned with, to be able to speak in a voice," recalled another. In 1954, Martha Evans , an exuberant redhead, became the first female member of the Charlotte City Council. She twice ran for mayor, against James Smith in 1959 and against Stan Brookshire and James Smith in 1961. Evans lost both times. In 1972, Myers Park resident Elizabeth or "Liz" Hair won a seat on the Board of County Commissioners and became chairperson of that body in 1974. A founding member of the Charlotte Women's Political Caucus , Hair was determined to advance issues that were especially important to women. She was instrumental in establishing the Mecklenburg County Women's Commission , the Council on Aging, and the adoption of the county's first affirmative action plan. She was responsible for the County's initial greenway master plan and was pivotal in saving the historic First Baptist Church in 1977 as the home of Spirit Square . Betty Chafin, now Betty Chafin Rash , was also an early leader of the Charlotte Women's Political Caucus . Born in Atlanta and reared in Winston-Salem, Chafin came to Charlotte in 1965 and soon started devoting much of her energy and talents to broadening the base of political participation in this community. Elected to City Council in 1975, she became a champion for ending the totally at-large system of electing members to that body. It had been that arrangement, enacted in 1917, that more than anything else had assured that white males would dominate local government. "Almost the whole council lived in one quadrant of the city," declared one of Chafin's allies. "This whole community was being governed by a slice of pie which if you'd eaten it, you would've eaten up southeast Charlotte." District representation was the "product of no blue-ribbon committee, Chamber task force or uptown bankroll," wrote Charlotte Observer columnist Jim Morrill. It was the "result of a small group of people who wanted to push more chairs around the public table." Sam Smith , a computer software developer, called it "as pure grass-roots an effort as you'll ever see." Smith insisted that Charlotte's Westside was the "stepchild" of the city and would never receive just treatment until it was more adequately represented on City Council and on other elected and appointed committees and agencies. Smith recruited other Westsiders, including truck driver Marvin Smith , and leaders of Charlotte's emerging neighborhood movement to back his efforts Bill McCoy of the Urban Institute at UNCC assisted Smith and his supporters in developing a plan for having City Council consist of seven district representatives and four at-large representatives. John Belk , son of New South retailer William Henry Belk , was mayor from 1969 until 1977. A millionaire, Belk vigorously opposed district representation. On October 11, 1976, he took the unprecedented step of vetoing a resolution calling for a referendum on the issue. Rash and the other three members of City Council who had supported the initiative were stunned. "All we wanted," explained City Councilman Neil Williams , "was the chance to submit the proposal to the people."

According to Belk, a specific scheme had to be presented to the voters. "Being for district representation is like being for motherhood," he declared. "In my opinion, you've got to find out who your mother is before you come out for motherhood." Belk insisted that district representation was not a priority issue. Wrangling over district boundaries, he argued, would take inordinate amounts of time and would divert public attention from the more urgent need to consolidate city and county governments. "I think the main thing that needs to be worked out is consolidation of the city and county," said Belk during the debate on October 11th. Much like his father, Belk believed that corporate executives and their lieutenants could provide the best government for all. "When you've got a winning team," he maintained, "you ought to leave it alone" Mayor Belk contended that "district representation would impede growth of the city, create 'horse trading' among council members and mean that the district council members would not represent the city at large on some issues," writes Alex Coffin in his book, Brookshire & Belk. Sam Smith and his allies overcame Belk's veto by gathering thousands of names on petitions to force a referendum. "We won in the face of a lot of power," said Smith. The voters of Charlotte narrowly approved district representation for City Council on April 19, 1977. Blacks broke their traditional alliance with southeast Charlotte and sided instead with middle class and lower middle class white precincts in west, north, and east Charlotte and with neighborhoods such as Dilworth . A reporter for the Charlotte Observer understood the import of what had occurred. "When neighborhood groups in north, west, and east Charlotte combined with a substantial majority of black voters to pass district representation Tuesday, they said goodbye to a long tradition in city government -- the domination of City Hall by well-to-do business leaders from southeast Charlotte." The establishment of district representation on City Council in 1977 and the eventual adoption of similar arrangements for the Board of County Commissioners and the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board in the 1980s sounded the death knell of the political system that the New South leaders had established at the turn of the last century. "The result," says Alex Coffin, "was that fewer payroll-meeting businessmen -- or businesswomen -- were elected thereafter." Not surprisingly, there was a concerted effort by some business executives to abolish district representation. In 1981, the citizens of Charlotte defeated that initiative. They went to the polls and said "yes" to continuing the new system by a margin of 11,023 votes. The days of unrivaled political hegemony by Charlotte's business elite were over.

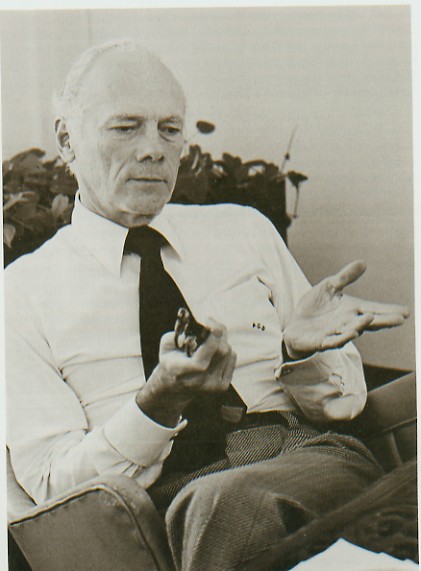

The architecture and urban design plans for Charlotte-Mecklenburg of this era also reflected the profound changes that were occurring in this community in the years immediately following World War II. Especially noteworthy in this regard is the work of A. G. Odell, Jr. A. G. Odell, Jr., the flamboyant son of a Cabarrus County textile executive, studied architecture at Cornell University and came to Charlotte in 1939 to establish a one-man office. By the time of his death in April 1988 Odell oversaw the operations of one of the largest and most influential architectural businesses in North Carolina. "In a society where class connection still counted for much, young Odell had automatic entry to the offices of the area's mill owners and businessmen," writes historian Thomas Hanchett. When Odell arrived, Charlotte’s buildings were overwhelming conservative and revivalist in appearance and had been so for decades. "Most architecture in the area can best be described as pseudo-neoclassical, with elements of design copied from buildings elsewhere that had already incorporated copied elements of classic design," remembered M. H. Ward, one of Odell’s early associates. A. G. Odell, Jr. became Charlotte’s principal champion of the International style and devoted his considerable talents and energies to reshaping the local urban landscape. For good or ill, he largely succeeded. Odell embraced the architecture of "tomorrow" and had nothing but disdain for the revivalist buildings he observed on the streets of Charlotte. One of Odell's earliest surviving International style houses is the Robert and Elizabeth Lassiter House at 726 Hempstead Place in Charlotte. Built in 1951 in the otherwise traditionalist Eastover neighborhood, the Lassiter House exhibits the exuberant boldness one finds in Odell's designs. A friend of attorney Robert Lassiter, Odell worked closely with Lassiter's wife Elizabeth in developing plans for the house. Steel beams support the roof and eliminate the need for load-bearing interior walls, thereby enabling large open spaces to predominate throughout the interior. A particularly ingenious scheme was an arrangement whereby the dining table could be set in the kitchen, complete with food and adornments, and slid through the wall into the dining room, where guests could witness the dramatic arrival of the entire repast.

Another of Odell's early home designs is the Goldstein House (1958) on Merwick Circle. Fashioned by Albert Cameron, an architect in Odell's firm, the house is modest in size but dramatic in impact. The fundamentals of the International style centered upon the exploitation of new materials, especially reinforced concrete, strengthened steel, and large expanses of glass, to create grace, airiness, and to allow great amounts of sunlight to penetrate the interior of structures.

The exposed rafters and lavish use of glass are typical of the Modernist style. It was in the area of urban design that A. G. Odell, Jr. was to have his greatest impact upon Charlotte. Odell took his lead from the thinking of such revolutionary post-World War One European architects as Le Corbusier. From about 1920 until shortly before his death in 1965, Le Corbusier was an untiring proselytizer for what he called the "Radiant City." To his way of thinking, urban designers should break completely with the past. Le Corbusier had no sympathy or interest in the preservation of existing buildings or neighborhoods. "Modern town planning comes to birth with a new architecture," he proclaimed. Le Corbusier envisioned people living in high rise apartments surrounded by lustrous skyscrapers separated from one another by large expanses of manicured open space and dramatic fountains. Urban cores should be hygienic, antiseptic, and ordered -- not cluttered, begrimed, and haphazard. The tradition of mixing functions in a single structure or neighborhood was an anathema to Corbusier. The city of the future would be divided into discreet sections devoted to specific purposes – working, living, leisure – connected to one another by expressways.

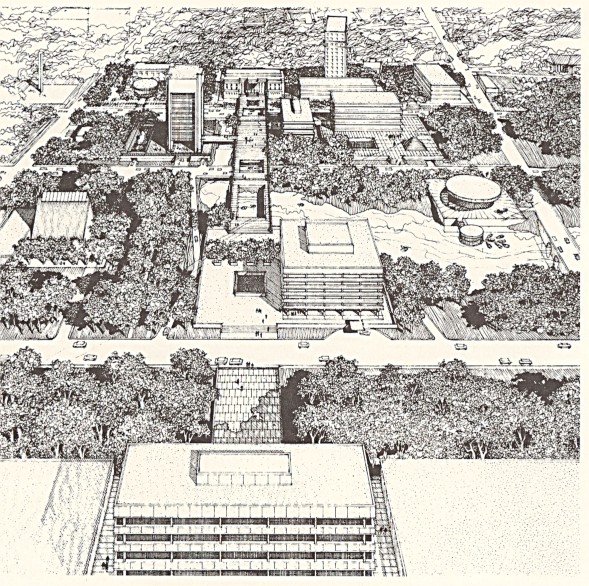

In 1965-66 Odell and Associates developed a comprehensive plan for the remaking of Center City Charlotte. It reflected his iconoclastic philosophy and established the fundamental parameters of uptown development for more than two decades. The plan continues to have considerable impact today. The initial impetus for the remaking of Center City Charlotte originated with the Downtown Charlotte Association in the early 1960s. Convinced that the urban core was spiraling downward in the face of growing suburbanization, the Association hired Hammer & Associates, economic consultants, in early 1963 to study what Center City Charlotte needed. The Hammer Report determined that new stores, green space, parking garages, and new entertainment facilities were required. It was this report that induced the Downtown Charlotte Association to hire A. G. Odell and Associates in 1965 to devise the Center City Plan, which was officially released in September 1966.

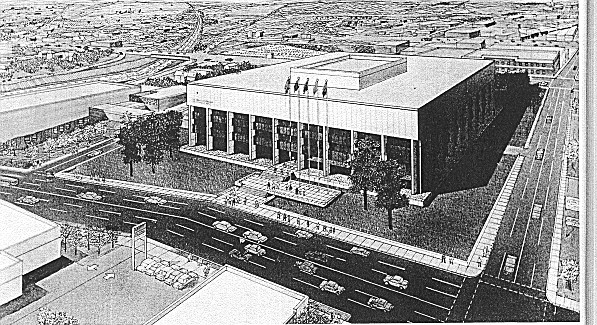

Odell benefited from the temper of his times. The 1960s and 1970s in Charlotte-Mecklenburg and the United States as a whole were decades of buoyant optimism, the persisting unpopularity of the Vietnam War notwithstanding. An eagerness to greet the challenges of the future and an almost total rejection of history and its architecture dominated elitist thinking. In a speech to the Charlotte Civitan Club’s 1966 Distinguished Citizens Award Ceremony, Dr. John T. Caldwell, Chancellor of North Carolina State University, advanced the commonly held assumption of that day that focusing upon the past was counterproductive to "progress." Charlotte "is a community filled with optimism for the days head, or it is a city enjoying a past that probably never was," he declared. Caldwell continued: "Charlotte is a city which is captive to the mores and fears of the past, or it is a community which greets the new demands of contemporary America with resilience at least and with eagerness at best." The Charlotte Observer sounded a similar tone. The newspaper was a consistent champion of the growth and expansion of Charlotte and its environs. Predictably, it issued a call for aggressive implementation of Odell’s Center City Plan when it was presented to the Charlotte City Council in March 1966. The editorial page contended that "Charlotte . . . has been studied enough. Those concerned about making this a more functional, more attractive city will now begin to act." The Charlotte Observer chided City leaders again in July 1966 for their alleged record of sluggishness in moving ahead with daring innovations. "Past councils have been much too reluctant to act with boldness and determination in redevelopment," the newspaper proclaimed. On March 2, 1966, James Rouse, the visionary developer of the planned community of Columbia, Md., trumpeted the same message in a stirring address he gave to attendees at the first annual UNCC Forum. He argued that unless Charlotte acted quickly and boldly it could squander its chances for becoming "one of the country’s most glorious cities." According to Rouse, the people of Charlotte stood "on the threshold of opportunity." To step back from the challenge, he insisted, would propel Charlotte in the wrong direction. "You can also succeed in reaching the point where the big, ugly cities are now. And you will surely get there if you don’t plan with boldness and vision," Rouse maintained. Not surprisingly, the Charlotte Observer rushed to endorse Rouse’s remarks. "Charlotte, as the major city of the Carolinas, can plan, can grow in an orderly manner, can become a city of the future," the editors declared. "But its citizens will have to have their minds stretched again and again." Odell’s Center City Plan was bold and visionary. Voters had approved a bond referendum the previous year to fund street improvements in the Center City; and the leveling of virtually every structure in the Second Ward or "Brooklyn" neighborhood, a large African American enclave, was already proceeding apace.15 Building upon these initiatives, Odell proposed a series of audacious initiatives. Like Le Corbusier, Odell embraced the philosophy of the "Radiant City." His plan predicted that visitors would "be coming to a new Charlotte, a Charlotte built anew with imagination, with sound economic reasoning, with a full knowledge that Charlotte’s position of leadership in the Carolinas and in the Southeast is one which the city deserves."16 What the Charlotte Observer called "swaths of expressway construction" would enable suburbanites to drive their automobiles more easily to the urban core.17 Parking decks would be built to house all the additional cars coming to the Center City, and all curbside parking would be eliminated. The intersection of Trade and Tryon Sts. would be transformed into a true "Square" by creating a plaza at the southeastern corner bordered by a hotel and retail shops. Odell, much in the tradition of the International style, advocated the creation of residential districts defined by parks and high rise apartment buildings. The plan called for the destruction of all the older homes in Fourth Ward, which the Charlotte Observer termed a "slum." Edwin Towers, a high rise apartment building for the elderly, was then under construction and apparently was the type of structure Odell envisioned for much of Fourth Ward. The plan advocated the burial of all utility lines and the removal of the railroad tracks between College and Brevard Streets and the turning of the rail line into a "Convention Boulevard." The most crucial element of Odell’s Center City Plan, what the Charlotte Observer called its "spark," was the construction of a Convention Center at the corner of South College St. and East Trade St. John A. Tate, Jr., Chairman of the Committee for the Master Plan, underscored the urgency of proceeding with the building when he spoke to the Charlotte Rotary Club on June 14, 1966. "The convention center is the ‘heart’ of the master plan for downtown revitalization," Tate insisted. "It is the ‘trigger’ and the ‘stimulant’ for redevelopment of the first block of South Tryon Street." The story of how the Convention Center got built is a tortuous and twisted tale The schedule for erecting the Convention Center was sidetracked on several occasions, but the City finally began constructing the facility in October 1971. "We’re concerned that this building will have a character of its own that will symbolize Charlotte in the eyes of the nation," said A. G. Odell. Odell promised that the Charlotte Civic Center, as it became called, "will compare with any in the country." The building opened with great fanfare on September 9, 1973. Ironically, the Charlotte Civic Center, which has been replaced by a new, larger convention center, stands empty today; and its future is in great jeopardy. In this writer’s opinion, the 1973 Charlotte Civic Center demonstrates a major weakness of the International style. The building’s most distinctive features are large pyramidal skylights that are only visible from a perspective several hundred feet in the air. While perhaps impressive as part of an architectural model, the Charlotte Civic Center presents blank brick walls to the pedestrian and provides no vitality or life to the streetscape. This criticism in no way detracts from the historic importance of the building, however. The Charlotte Civic Center did stimulate large-scale real estate developments on adjacent parcels, specifically the North Carolina National Bank Complex and the Radisson Hotel. The building was also the most crucial element in the implementation of A. G. Odell Jr.’s seminal 1966 Charlotte Center City Plan. The other leading proponent of Modernist architecture in Charlotte was J. N. Pease Associates. In the early 1960s, the editors and production staff of the Charlotte Observer saw the need to expand the newspaper’s home so that more presses could be brought on line and more space could be provided for its various departments to keep up with growing circulation. General Manager Bill Dowd considered several sites, including suburban tracts off Interstate 85; but he and publisher Jim Knight preferred locations in the Center City. "Dowd feared that the newspapers’ move to the suburbs at that juncture would cripple downtown," writes Jack Claiborne in his history of the Charlotte Observer. It is not surprising that the Observer wanted a contemporary, non-traditional style building for its home, since the newspaper had consistently championed Charlotte as a "progressive place."

Real Estate agent Louis Rose succeeded in assembling the entire block surrounding the building the Charlotte Observer had occupied at the corner of South Tryon St. and W. Stonewall St. since 1927. Dowd made the announcement in December 1965 that the Charlotte Observer would not move to the suburbs but would construct a new building on the tract that Rose had put together. "We are particularly pleased," he proclaimed, "that our newspapers are to remain in downtown Charlotte, and we are hopeful that the developments we have in mind will be an enhancement of downtown and a stimulus to plans for revitalizing the central business district." The Charlotte Observer moved into its new Center City home in 1972. J. N. Pease Associates, a Charlotte-based design and engineering firm, was the architect of the new Charlotte Observer Building. J. Norman Pease, a native of Columbus, Ga., and James A. Stenhouse, born in St. Louis, Mo. but a resident of Charlotte from early childhood, co-founded their company in 1938. The building of Fort Bragg and the hiring of J. N. Pease Associates to provide architectural and engineering services for the massive military base gave a great boost to the firm. The success of J. N. Pease Associates continued after World War Two as Stenhouse and Pease competed successfully for major projects, including the new home of the Charlotte Observer. Commenting on Pease’s career, the Charlotte Observer stated: "So sweeping was his presence, most Charlotte residents have probably worked in, banked in, studied or prayed in one of his products." J. N. Pease Associates, in addition to many other projects, designed Edwin Towers in Fourth Ward, most of the buildings at Central Piedmont Community College, developed a master plan for the expansion of the government center in Center City Charlotte and fashioned most of the buildings and spaces created therein, including Marshall Park.

Pease, who had moved to Charlotte in 1920 to open an office for Lockwood Green, an engineering firm, was an engineer, not an architect. He believed that by offering a wide range of services, including having its own structural, electrical, and mechanical engineers, J. N. Pease Associates could win contracts to design and oversee the construction of municipal facilities, such as governmental office buildings, sanitary plants and water treatment works for cities. Pease was also eager to provide design and engineering services for clients in the private sector. Not surprisingly, especially in the post-World War Two years, J. N. Pease Associates became an advocate of the Modernist style. The School of Design at North Carolina State championed Modernism after the arrival of Henry Kamphoefner as dean in 1948, and many of its graduates joined firms like J. N. Pease. Also, as noted earlier, A. G. Odell, Jr. had established his office in Charlotte in 1939 and had become an ardent advocate of Modernism. A final factor in inducing J. N. Pease Associates to embrace Modernism was the influence of J. Norman Pease, Jr. Trained in Modernist principles at Auburn University, the younger Pease joined his father’s firm after World War Two and replaced Beaux Arts-trained James Stenhouse as chief designer.

According to Claiborne, the design of the Charlotte Observer Building was inspired by the headquarters of the Miami Herald, then the home newspaper of the Knight Publishing Company. The intent was to erect an "imposing castle," a structure that would communicate to the public the importance of the Charlotte Observer to the community and the region. The influence of Modernism upon the design is obvious. In keeping with Swiss architect Le Corbusier’s notion of the "Radiant City," which J. Norman Pease, Jr. had studied at Auburn along with the ideas of such exponents of Modernism as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, the building is devoid of lavish decoration, uses its essential form and the employment of contemporary materials to convey its significance, and is surrounded by a manicured lawn and landscaping.

|