|

Chapter Four

Gold and Railroads Dr. Dan L. Morrill University of North Carolina at Charlotte E-mail comments to N4JFJ@aol.com

Cotton was not the only source of wealth in ante-bellum Mecklenburg County nor the only enterprise that depended heavily upon slave labor. Industrialized gold mining became serious business in the Carolina Piedmont in the first half of the nineteenth century and made Charlotte, as over against Mecklenburg County, an important economic center for the first time in its history. Charlotte "was a quiet little village, and seemed to be kept up principally by the mining interest," declared an English geologist who visited here in October 1837. In 1799, Conrad Reed , the twelve-year-old son of John Reed, a Hessian soldier who had fought for the British in the Revolutionary War, was fishing with a bow and arrow along Little Meadow Creek on the family farm in Carbarrus County. Suddenly he saw a distinctive seventeen-pound rock and decided to take it home, where it was used as a doorstop for three years. A jeweler in Fayetteville identified it as gold in 1802. This was the opening event in the history of the gold mining industry of North Carolina, which extracted $60 million of the precious ore between 1799 and 1860 and led the nation in gold production until the discovery of large deposits of the metal in California in 1848. Click here to visit the Reed Gold Mine Historic Site. News traveled slowly in the sparsely settled agrarian society of the North Carolina Piedmont in the early 1800s. There was no immediate gold rush. Until the mid-1820s, farmers took a haphazard approach to mining for the precious ore. "It is laughable," wrote one visitor, "to see these tall, long-tail cotton-coat North Carolinians . . . poking about like snails, and picking up the quicksilver every now and then, and eagerly squeezing it in their hands, to see how much gold is in it." Few people laughed when a laborer at the Reed Gold Mine gathered fourteen pounds of gold before breakfast and five more pounds before sunset. One geologist reported that workers "dug the gold 'like potatoes.'" "Several individuals in North Carolina. . . have been eminently successful," reported the Miners' & Farmers' Journal, a promotional publication of the mining industry.

It did not require a lot of capital to become involved in gold mining in the early 1800s. All the equipment someone needed to get started was a pick, a shovel, a pan, and a strong back. After the fall harvest, when they had little else to do, families, including their slaves, would inspect creek beds or dig shallow holes, called placer pits, to see what they might find. A geologist who visited the Reed farm in 1825 observed that the ground bordering Little Meadow Creek "has been nearly all dug over, and exhibits at present numerous small pits for the distance of one fourth of a mile on both sides of the stream." Mecklenburg County still has hundreds of placer pits. A good place to see a few examples is the McIntyre Historic Site on Beatties Ford Road.

The unsystematic, low cost approach to gold mining began to subside in 1825. Matthias Barringer , a farmer living in what is now Stanly County, noticed that gold was especially prevalent in veins of white quartz rock. The implications of this discovery were revolutionary. Miners who heretofore had dug placer pits on the surface of the earth suddenly realized that they would extract a lot more gold by sinking shafts deep into the red hills of the Piedmont. Shaft mining, however, was costly. It took a great deal of money to establish mines of this sort, and North Carolina farmers had little expertise in such enterprises. The solution was to attract foreign capital and labor. Charlotte, like many other tiny villages in the Piedmont, became a boomtown almost overnight in the early 1830s. After sizeable deposits of gold were discovered at Sam McComb's St. Catherine Mine , hundreds of laborers began arriving from places like Great Britain, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. "The discovery, near Charlotte in 1831, of a nest or bed of gold containing pieces weighing five, seven and eight pounds . . . produced a frenzy of excitement," writes historian Fletcher Green. Nine gold mining companies doing business in Mecklenburg County had received their charters of incorporation by 1834. The largest was the London Mining Company, which leased the St. Catherine Mine and the Rudisill Mine in the vicinity of what is now Bank of America Stadium and Summit Avenue in Charlotte. It brought Italian mining expert Count Chevalier Vincent de Rivafinoli to oversee its local operations. A flamboyant, elegant dresser, Rivafinoli made a strong impression upon the Scots Irish residents of Charlotte. According to one observer, the Count was "a gentleman of science and practical experience, having been acquainted with the mines in Mexico and Germany."

Most of the new arrivals in Charlotte possessed none of Rivafinoli's refinements. They were the type of individuals one usually finds in towns on the mining frontier. A correspondent for the New York Observer toured the North Carolina gold fields in 1831 and was appalled by what he saw. "I can hardly conceive of a more immoral community than exists around these mines," he exclaimed. "Drunkenness, gambling, fighting, lewdness, and every other vice exists (sic.) here to an unlawful extent." A reporter from Charleston, South Carolina expressed similar dismay, noting that "business is (sic.) neglected through the week, and even the churches deserted on the Sabbath, to search for the corrupting treasure!" Some local citizens fell victim to the shameful influences of gold and the sudden wealth it could provide. One such person was James Capps . A poor farmer residing on a tract of "sterile & apparently valueless land" off Beatties Ford Road about five miles north of Charlotte, Capps discovered gold on his impoverished farm and leased it to foreign investors in 1827. The Capps Mine became the "most productive gold mine in Mecklenburg County, and perhaps in the state," declared the Western Carolinian. Suddenly affluent, Capps began carrying portable scales with him wherever he went, so he could weigh the gold dust he needed to purchase whatever he wanted. Unfortunately, Capps used most of his precious ore to buy whiskey. He died from alcoholism in 1828. A newspaper reporter declared that "the BOTTLE, that too common resort of those whom affliction has cast down, or some freak of fortune has suddenly elevated to a condition for which nature had unsuited them, cut short the days of this miserably fortunate old man!"

Gold mines were not pretty places. They were noisy, smelly, grimy, and dangerous. The first step in establishing a shaft mine was to erect housing for the work force that included emigrants, poor farmers, women, children, and slaves whom local slave owners rented out to mining enterprises or whom the companies owned outright. "Taken collectively, southern companies owned directly eighty percent of the total slaves engaged in industry," writes Jeffry Paul Forret in his U.N.C.C. Masters Thesis. The remaining twenty percent were nothing more than rental property.

Leasing bondsmen and bondswomen was a widespread practice in the ante-bellum South. According to one estimate, 6 percent of rural slaves and 31 percent of urban slaves were on lease from their masters in 1860. Mining companies preferred renting slaves to buying them outright because it cost them less money. A mining agent placed the following advertisement in a Charlotte newspaper in 1835. I wish to hire from 15 to 25 NEGROES, to be employed in the Gold Mines near Charlotte. The highest price will be given for good hands; and those having some experience in the business will be preferred. Gentlemen having slaves whom they wish to hire advantageously, will please call on me. It was not uncommon for slaves to flee from their masters in hopes of finding work in the North Carolina gold mines. The pitiless blacks, aspiring to find enough gold to purchase their freedom, were generally assigned such menial tasks as cutting timber, building fences and dams, and growing hay, corn, and oats for the miners and for the company's mules and horses. One Cabarrus County slave owner complained in 1831 that "his boy Lewis" had left home to "sculk (sic.) about the gold mines in this county and Mecklenburg." Slaves could sneak off in their spare time and search for deposits of the precious ore and were allowed to keep a certain percentage of the gold they discovered. The Capps Mine had 38 slaves on its workforce in 1831, including 10 women. The majority of the workers in the gold mines of North Carolina were foreigners. "In 1830 alone, Charlotte's population of 717 included sixty-one unnaturalized foreigners," writes historian Jeffrey Forret. The largest number had come from Cornwall in southeastern England, where they had learned the techniques of underground mining by extracting tin and copper for centuries. Illustrative of this truth are the words of a favorite Cornish toast, "fish, tin, and copper." The home of one Cornishman, Richard Wearn , who came to Mecklenburg County in 1831, still stands on Tuckaseegee Road. He bought this land in 1837 and erected the oldest portion of his house in 1846.

Richard Wearn House Another native of Cornwall who emigrated to the North Carolina gold mines was John Gluyas . The Mecklenburg Gold Mining Company persuaded Gluyas to move from New York City to Charlotte in 1838 by paying him a salary of $84 per month and by providing him lodging and covering his traveling expenses. Gluyas's first job was to oversee the steam-powered machinery at the Capps Mine. He would eventually become superintendent of mines in Mecklenburg, Cabarrus, Davidson, and Montgomery counties. His son's house, the Thomas and Latitia Gluyas House , is a designated historic landmark on the Mt. Holly Huntersville Road.

Picture what you would have seen and heard if you had visited the St. Catherine Mine at Charlotte sometime during the mid-1830s. An awe-struck itinerant preacher called one Mecklenburg mine "the greatest sight that I ever saw." Another visitor called the St. Catherine "the greatest establishment" he had ever encountered. Even from a distance you would have known that a gold mine was nearby. The unmistakable thud of the stamp mill's weights would have told you that rock was being pounded into small bits. The hissing of the steam engines that powered the pumps that removed water from the underground tunnels would also have pricked your ears. As you got nearer, a cluster of buildings would have come into view on the ridgeline just outside Charlotte. Simple, utilitarian wooden structures, they would have included a large windlass over the main vertical shaft, where a blind horse or a blind mule would have been circling endlessly to provide power for the cumbersome device that continuously lifted buckets of white quartz rock to the surface.

A newspaper reporter from Charleston, South Carolina toured the St. Catherine Mine in 1831. "I went down a ladder about one hundred feet, perpendicular, and thence along galleries well braced on the sides, and roofed with boards overhead, for some hundred feet further," he declared. "I then followed, in a slanting direction, the vein to the spot where the miners were taking the ore from the earth, and sending it aloft by means of buckets, which are drawn up by mules." The underground workers wore short-sleeved coats and white overalls. "A round-topped, wide-brimmed hat of indurated felt protected the head like a helmet," wrote a reporter for Harper's Magazine. "In lieu of crest or plume each wore a lighted candle in front, stuck upon the hat with a wad of clay." The pace of gold mining in North Carolina began to wane in the late 1830s and early 1840s. The national economic downturn known as the Panic of 1837 hastened the ruin of many unwise speculative investors. "Led on by bankrupt merchants, broken-down lawyers, quack doctors, clergymen whose political fanaticism had robbed them of their churches -- in short, officered by men who had failed in every pursuit they had undertaken -- how could it be otherwise than that the operations, conducted by them in this new field of enterprise, would have been attended with the same failures which had marked all their former doings?", commented one observer. Even more significant in prompting miners to abandon their operations in North Carolina was the discovery of huge gold deposits in California in 1848. Southern miners simply packed up their belongings and departed individually and in groups for California, many taking their slaves with them. "One stream in McDowell County which had 3,000 miners at work in 1848," writes historian Fletcher Green, "was practically deserted in 1850." All that remained were abandoned wooden buildings and piles of white quartz rock. Some gold mines did continue to operate in the North Carolina Piedmont, some as late as the Great Depression of the 1930s, but never even close to the level of activity of ante-bellum days. The most significant building that survives from the gold mining era in North Carolina is the former United States Branch Mint in Charlotte . It was dismantled and moved from its original location on West Trade Street in 1936 and now serves as the Mint Museum of Art . Designed by renowned Philadelphia architect William Strickland , the facility opened for business on December 4, 1837, under the direction of Superintendent John H. Wheeler . The need for a branch mint in the North Carolina gold region arose because of the tendency of many private assayers and minters to produce counterfeit coins. A Congressional committee reported that a lot of "imperfect currency" was circulating in and around Charlotte and the other boomtowns of the Piedmont. The imposing new edifice, which cost $29,700 to build, operated until Confederate authorities took it over in May 1861.

Grand buildings were also erected on the campus of Davidson College in the 1830s and 1840s. The leaders of the Concord Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church, not wanting their sons to continue having to go to Princeton College in New Jersey to receive a Calvinistic education, voted on March 12, 1835, to establish an institution of higher learning in western North Carolina. William Lee Davidson, II was a member of the committee charged with selecting a site for the "Manual Labour School." He was also the son of General William Lee Davidson , who had died on February 1, 1780 in the Battle of Cowan's Ford . At a meeting held at Davidson's home, Beaver Dam , on May 13, 1835, "at candlelight after solemn and special prayer to Almighty God for the aid of his grace," the committee decided to recommend purchase of 469 acres of Davidson's land for $1521 for the college's campus. At a later meeting, on August 26, 1835, it was decided to name the institution "Davidson College" ... as a tribute to the memory of that distinguished and excellent man, General William Davidson , who in the ardor of patriotism, fearlessly contending for the liberty of his country, fell (universally lamented) in the Battle of Cowan's Ford .

Davidson College opened in 1837. The original curriculum included moral and natural philosophy, evidences of Christianity, classical languages, logic, and mathematics. There were three professors, including Robert Hall Morrison , who was also the college's first president, and approximately sixty-four students. The oldest extant structures on the campus are Elm Row and Oak Row . Both were originally dormitories and date from the first year of the institution's operations. The style and placement of the buildings suggest that the Presbyterian elders who founded Davidson College were hoping to duplicate the feel of Thomas Jefferson 's famous "Lawn" at the University of Virginia. The exteriors of the buildings retain their original Jeffersonian Classical features. The most elegant of the early college structures are Eumenean Hall and Philanthropic Hall . Both were built in 1848, and each served as the home of a debating society, secret and formal in nature.

The rules of the debating societies were very strict about the behavior of members. Fines were imposed for fighting, swearing, intoxication, or "lying to the faculty." There were even "vigilance committees" for reporting offenses. Since nearly all students were members of one society or the other, "student government really dates from the beginning," with the regulation of behavior coming from the two societies. It is said "around the two halls centered college loyalty and affection." The societies provided excellent libraries and financed almost all the annual commencement activities. Despite their good intentions, the two literary societies were not always successful in controlling the deportment of their members.

On August 10, 1853, the Board of Trustees

of Davidson College

voted to invite Daniel

Harvey Hill

to become a Professor of Mathematics at their fledgling

institution of higher education. A

graduate of West Point and veteran of the Mexican War,

D. H. Hill was thoroughly familiar with Davidson.

His father-in-law was Robert Hall Morrison

. Even though he was

quite content to remain on the faculty of Washington College

in Lexington, Virginia., where he had "received not a single

mark of discourtesy, or disrespect," Hill accepted the position at

Davidson, largely because of his "desire to labor in a College,

founded in the prayers, and by the liberality of Presbyterians."

Also, the Board of Trustees had agreed to support his "views . . . in

regard to the standard of education, and system of government of the

College." C. D. Fishburne

, a former student at Washington College and a colleague

of Hill's on the Davidson faculty, explained

that Hill "entered on his duties with the assurance that he would be

heartily sustained by a large majority of the Trustees in every effort he

might make to completely change the College, in the standards of

scholarship and behavior."

What happened over the next five

years at Davidson College

illustrates just how

tenacious and persistent "Harvey" Hill could be. Nothing could

seemingly dissuade this man from trying to attain an objective once he had

decided to pursue it. To

put matters bluntly, the Board of Trustees wanted Hill to take charge and

subdue the violence that was threatening to destroy the college.

"Major Hill was . . . induced to accept the place by the urgent

request of prominent friends of the College who were dissatisfied with its

condition," said Fishburne. The 33-year-old South Carolinian was

eager to meet the challenge. The behavior of Davidson's students, like that on many other college campuses in the South, was raucous and unsettling. Many of the approximately 90 students were virtually out of control. Riots were common. Drinking and carousing were widespread. If suspended, troublemakers would not go home, largely because they did not have enough money to pay their way. Waiting to be readmitted, they would walk around campus or sleep all day in the town's boarding houses. Even worse, at night, under the cover of darkness, they would entertain themselves by making mischief, much of it mean spirited. On Thursday, December 22, 1853, for example, students attacked the houses of two professors with rocks and eggs and set off several bombs on the campus, "the report being heard some four or five miles around the College." On Friday, April 21, 1854, a "wooden building was demolished" during a campus riot. One student even put gunpowder into a candle snuffer, which exploded when it was used. The unsuspecting owner suffered serious damage to one eye. After fulfilling his obligations at Washington College, Hill arrived in Davidson on May 28, 1854, and almost immediately began implementing major changes in the academic program. Uppermost on his agenda was the installation of the same military grading system of merits and demerits used at many colleges during the 1850's, including Washington College and West Point. Not a few students, Hill insisted, had been "allowed to trample upon all laws, human and divine." These surly youngsters had an "undisciplined mind, an uncultivated heart, yet with exalted ideas of personal dignity, and a scowling contempt for lawful authority, and wholesome restraint," he lamented.

Hill insisted the he knew how to end such fractious behavior. Never one to mince words, especially when he believed that somebody in authority was incompetent, Hill lashed out at Samuel Williamson , the College's president. "The character of a College depends mainly upon the character of its President," Hill told the Board of Trustees. In August, 1854, Williamson resigned when it became clear that the combative new mathematics professor was going to prevail. Hill also offered to quit, but the Board of Trustees insisted that he stay. As promised, the Board of Trustees approved Hill's new grading system of merits and demerits, on August 8, 1854. The most severe punishment was bestowed upon those students guilty of "profanity, fighting, disorderly conduct in recitation rooms, in Chapel, or on the Campus." There were also severe penalties for students "being improperly dressed." Clearly, a restrictive new regime was taking control at Davidson College , and Daniel Harvey Hill was its indomitable leader. The days of lax discipline were over. The minutes of the Davidson College Faculty are replete with examples of professors, especially D. H. Hill, subjecting students to exacting regulations. These included unannounced inspections of dormitory rooms to make sure that students were studying, informing parents when their children were "too frequently absent from College duties," and reading each Monday in Chapel a "list of the delinquencies and offenses" that had occurred the pervious week. ". . . on account of noise on the campus, Profs. Hill and Fishburn (sic.) inspected the College Buildings and found that Messrs. Bailey, and R. B. Caldwell were absent from their rooms," the Faculty minutes declared on one occasion. D. H. Hill was particularly concerned about students drinking whiskey. The minutes of one meeting stated: Faculty met, and after the usual business, some

conversation was had about certain students being addicted to drinking,

and it was reported that a citizen of the village had informed a member of

the Faculty that there was a good deal of drinking this term among the

students. Where-upon, it was agreed, on motion of Major Hill, that the

Faculty visit the students' rooms one night of this week.

There was also anxiety about the presence of firearms on campus. The Faculty stipulated that "no student be allowed to use fire-arms (sic.), except on Saturday, and at no time on the College premises." The new instruments of control even extended to visitors to the campus. In May, 1855, the Faculty hired policemen and directed them "to disperse negroes who may collect about the College on Sundays." It was against the background of these developments that a large number of students rioted with particular ferocity on the night of December 21, 1854. No doubt harboring deep resentments over the enforcement of Hill's restrictive measures, the participants in this uprising expressed their anger by lighting fires and throwing rocks and eggs at two professors' houses, including the home of J. R. Gilland , the president of the Faculty. Rocks flew through the air. One struck Hill in the forehead. Undismayed, blood dripping down his face, the feisty mathematics professor pressed the attack, just as he had done in the Mexican War and as he would do later in battle after battle with the Yankees during the Civil War. Gradually the students retreated and began to slip away into the darkness. Hill ordered the Faculty -- there were only four members -- to enter the dormitories to make sure which students had stayed in their rooms. All the students were either at their desks studying or asleep in their beds when the faculty entered. One room was locked. Hill smashed in the door with an ax, rushed in and found D. Newton, a known mischief-maker, feigning sleep but still wearing his boots. The repercussions of this student uprising were dramatic and profound, at least for Davidson College . An inquisition of sorts occurred the next day, when the entire student body was ordered to appear before the Faculty and explain their whereabouts the night before. Not surprisingly, everybody insisted that they had not taken part in the recent disturbance. On December 26th, the Faculty suspended D. Newton for three months for "his inattention to his studies, . . . his having used in a written essay disrespectful language to a Professor, and from the strong circumstantial evidence to convict him of participating in a riot on the night of the 21st." Forty-two students, more than 50 percent of those attending Davidson College, signed a petition requesting that Newton be allowed to remain. The document contended that convicting Newton on mere circumstantial evidence was "inconsistent with the principles of justice, and contrary to the dictates of reason." When D. H. Hill and his colleagues refused to adhere to the their wishes, the protesting students left school, many never to return. Daniel Harvey Hill did not seek to be popular. In his opinion, neither should colleges. Too many colleges and universities, he insisted, had become little more than "polishing and varnishing" institutions, because they did everything necessary to maintain their enrollment, including sacrificing academic standards. And what kind of graduates did such places produce? "An occasional scholar is sent out from their walls, whilst thousands of conceited ignoramuses are spawned forth with not enough Algebra to equate their minds with zero," Hill proclaimed in his official inaugural address to the Board of Trustees on February 28, 1855. " . . . ninnies take degrees," the acerbic major continued, "and blockheads bear away the title of Bachelor of Arts; though the only art they acquired in College was the art of yelling, ringing of bells, and blowing horns in nocturnal rows." D. H. Hill believed that human beings are by nature wretched and sinful creatures. "Self-abasement and self-abhorrence must lie at the very foundation of the Christian character," Hill wrote in 1858. Regardless of its origins, this predilection to emphasize the negative aspects of human deportment brought a certain harshness to Hill's rhetoric. Indeed, his inaugural address at Davidson was full of vituperative language. Without rewards for good behavior, the majority of students would "speedily acquire idle habits, and learn to drone away their time between lounging, cards, cigars, and whiskey punch," Hill maintained. And as for those miscreants who had no desire to improve their behavior, they would "congregate together around their filthy whiskey bottle, like ill-omened vultures around a rotten carcass." It was this tendency toward invective and pointing out the faults in others that caused many people to dislike Daniel Harvey Hill . But Hal Bridges, his biographer, reminds us that Hill was a man of many facets. "At every stage of his career, the attractive qualities . . . were liberally intermingled with his prickly traits of character," says Bridges. Davidson College derived enormous benefits from having "Harvey" Hill on its faculty. In addition to leading the effort to restore discipline, he labored tirelessly to strengthen the academic program. He persuaded the Board of Trustees to purchase new equipment for the Mathematics Department. He brought C. D. Fishburne to Davidson and agreed to pay Fishburne's salary for two years if the money could not be raised to meet this obligation -- no small commitment when his own annual salary was just $1705. Salisbury, North Carolina merchant Maxwell Chambers bequeathed $300,000 to the college in 1852. Ratchford insisted that Chambers was most pleased with the improvements that Hill brought about. "This I presume is the largest Legacy ever left to one College in the Southern States," said Robert Hall Morrison , D. H. Hill's father-in-law. Anyone doubting the importance of his contributions to the overall improvement of Davidson College need only read what the Board of Trustees said about D. H. Hill when he resigned from the faculty on July 11, 1859. That whilst we, as a Board of Trustees, accede to the

wishes of Major D. H. Hill, we accept his resignation with very great

reluctance, much regretting to lose from our Institution such a pure and

high minded Christian gentleman, diligent and untiring student; thorough

and ripe scholar, and able faithful, and successful Instructor --

especially in his Department -- as Major Hill as ever proved himself to be

since he came amongst us. In 1859, no doubt at D. H. Hill's urging, the General Assembly of North Carolina enacted legislation which assured that Hill's impact upon campus life at Davidson College would endure. The law stipulated that no person could "erect, keep, maintain or have at Davidson College, or within three miles thereof, any tippling house, establishment or place for the sale of wines, cordials, spirituous or malt liquors." It prohibited "any billiard table, or other public table of any kind, at which games of chance or skill (by whatever name called) may be played." The punishments for violating these prohibitions were severe, especially for slaves. They were "to receive thirty-nine lashes on his or her bare back." The departure of Daniel Harvey Hill from Davidson College came as no surprise. It was widely known that he was about to become the Superintendent of the North Carolina Military Institute in Charlotte. The decade of the 1850s was a time of propitious happenings in Charlotte. Indeed, those ten years witnessed to a substantial degree the birth of the community that we inhabit today, at least in terms of civic spirit. Unlike the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793 or the discovery of gold by Conrad Reed in 1799, both of which had profoundly impacted life in Mecklenburg County, local residents, not outside forces or good fortune, brought this new change about. "With our citizens, the tide and the spirit of improvements are still as high as ever," declared a Charlotte newspaper in 1853. There was considerable apprehension about the future economic health of the county after the Panic of 1837 and the discovery of gold in California in 1848. Physician Charles J. Fox and lawyers James W. Osborne and William Johnston led the effort to boost local development by bringing a railroad to Charlotte. By doing so, they elevated resolute and imaginative leadership to the pinnacle of importance it has occupied in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County ever since. There was nothing inevitable about Charlotte's becoming the leading city of the Piedmont. It took hard work, foresight, and imagination to achieve that objective. Mecklenburg planters like James Torance and W. T. Alexander produced bounteous crops of cotton throughout the 1830s and 1840s, but markets were far removed and difficult to reach. Teamsters had to traverse nearly impassable roads to Fayetteville, Cheraw or Camden, where the “White Gold” of the South was loaded onto flat-bottomed scows for shipment to Wilmington, Georgetown or Charleston. “The difficulties faced by farmers in marketing their crop led many to abandon the Carolina Piedmont for greener pastures in the west,” writes historian Janette Greenwood. Having experienced vigorous growth in the first three decades of the nineteenth century, the population of Mecklenburg County declined from 20,073 in 1830 to 13,914 in 1850. Although a substantial number of those no longer living in Mecklenburg had become residents of new neighboring counties, such as Union County, Mecklenburg County was unquestionably experiencing economic stagnation. Real estate values fell by about half during the same years. Clearly, dramatic action was needed if Charlotte-Mecklenburg was to continue to compete with other communities for economic prominence.

In 1847, Johnston, Fox, and Osborne began

sponsoring public meetings in Charlotte and its environs to champion a

rail line that would link Charlotte to Charleston by way of Columbia,

South Carolina. The railroad

boosters contended that only the laying of track and the arrival of

locomotives would allow the County’s farmers to enjoy “the

improvements and advantages of the age in which we live.”

They named the proposed line the Charlotte and South Carolina

Railroad

and insisted it would save

Mecklenburg County and its neighbors “from poverty and from ruin.”

Fundraisers were held in towns throughout

the region, including Lincolnton, Salisbury, Concord, Monroe, and as far

away as Rutherfordton. Typically,

Fox, Johnston or Osborne would travel by wagon to an evening banquet,

frequently held out of doors or in a tent, where they would preach the

wonders of the railroad as an instrument of progress and call upon the

members of the audience to come forward and buy stock.

The atmosphere was not unlike that at a religious revival, but in

this instance the message was entirely secular.

The response was overwhelmingly

positive. The farmers of the Providence community organized a barbecue and

pledged $14,000. A sizeable

home could be bought at that time for $3000!

By August 1847, the astounding sum of $300,000 had been raised for

the road. The dream of

connecting Charlotte to Columbia and Charleston by rail was going to

become a reality.

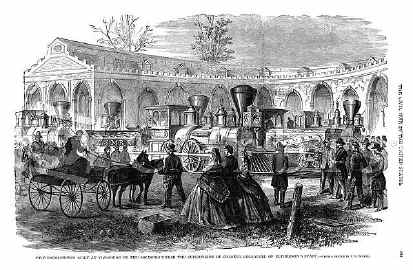

On October 28, 1852, a crowd of about

20,000 people – more than 15 times the population of the town --

gathered along the tracks that still parallel South College Street and

waited for the arrival of the first train.

For weeks the people of Charlotte had heard the whistle atop the

approaching locomotive announce at the end of each day how far the work

crews had come. All was anticipation and excitement. Then it happened.

Hissing and screeching its way north from Rock Hill, its plumes of

smoke signaling the opening of a new era, the train finally lumbered into

the Charlotte station, which was situated about where the Charlotte

Convention Center now stands.

More than any other event, the

arrival of the railroad in 1852 set Charlotte on its way to being the

largest city in the Carolinas," contends historian Thomas W. Hanchett.

Heretofore, nothing had distinguished Charlotte economically from

other towns in the southern Piedmont.

There had been no greater reason for farmers to congregate for

business here than in Lincolnton or Monroe or Concord.

The efforts of Fox,

Osborne, Johnston, and their supporters made Charlotte the railhead of the

region and its transportation and distribution center, a position it has

never relinquished.

"Our people seem to be inspired with

new life and new energies amounting almost to intoxication,"

proclaimed a local newspaper. Investors even began building commercial

structures in anticipation of the railroad.

Thomas Trotter

, William Treloar

and other local merchants began constructing a row of brick

commercial buildings, known as "Granite Row" or "Granite

Range," on the southwestern corner of the Square in July 1850 and

completed them in September 1851. Probably

the first brick store buildings in Charlotte, Granite Row was torn down in

the 1980s to make the center city "more attractive." Happily, William Treloar

's post-Civil War home survives at 328 North Brevard Street.

With Charlotte having the only rail

connection from the southern Piedmont into neighboring South Carolina, it

was only logical that the largely State-financed

North Carolina Railroad

, extending from

Goldsboro on the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad westward through Raleigh

to Greensboro and Salisbury, would terminate in Charlotte.

The first train traveled the entire route from Goldsboro to

Charlotte on January 31, 1856. "We now have a railroad connection

with Raleigh, Petersburg, Richmond, and with all the cities of the North,

on to the lines of Canada," the Western

Democrat

proclaimed.

In 1858, the Wilmington, Charlotte

and Rutherfordton Railroad Company

erected a passenger station

on North Tryon Street to serve as the eastern terminus of a thirty-one

mile line from Charlotte to Lincolnton, which was completed by April 1861.

Dr. Charles Fox headed the campaign to establish Charlotte's fourth

railroad of the 1850s, the Atlantic, Tennessee and Ohio Railroad

or AT&O, which despite

its boastful name only ran from Charlotte to Statesville. The Atlantic, Tennessee & Ohio Railroad reached from

Charlotte to Davidson in 1861 and to Statesville in March 1863, where it

connected with the Western North Carolina Railroad

.

Dr. Paul B. Barringer

of Concord rode the

AT&O as a child. His remarks provide a fascinating glimpse into the

early days of railroading in Mecklenburg County.

It took 8 hours to travel 4O miles.

"These engines burned nothing but wood, rich resinous pine

wood, and the sparks from the smokestack often set fields afire unless the

sparks were controlled by a sifter of fine mesh set in the upper part of

the smokestack," he reported.

Barringer explained that second-class passengers sometimes and

third-class passengers always had to "get out at every woodyard to supply the tender, their only notification being a

peculiar blow of the whistle."

Riding the train was an

exciting experience, partly because it was so

perilous. The base of

the track of the AT&O was wooden.

A flat-iron rail three-quarters of an inch thick and four inches

wide was attached by spikes to an oak beam

"This was all very well for a five to ten-ton load,"

Barringer observed, "but in time the spikes sunk through the rails

ceased to hold, particularly at the ends."

"The ultimate was reached," said Barringer, "when

the end spikes were thrown out, and the ends of the iron rail stood up,

perhaps on a cold day as much as eight to ten inches."

The primitiveness of railroad technology of

the 1850s notwithstanding, the daily arrival of passenger and freight

trains meant that Charlotte was no longer an isolated courthouse town. Merchants, including Jews, began to arrive and establish

mercantile houses during that decade. Among them were two German Jews,

Samuel Wittkowsky

and Jacob Rintels

. They met as

co-workers for storeowner Levi Drucker

, a leader of the

local Jewish community and owner of a mercantile establishment. Rintels

and Wittkowsky soon became partners in a large wholesale store and

prospered. Rintels, the more

flamboyant of the two, would eventually erect an imposing Victorian style

mansion on West Trade Street. The

house, which has been moved and altered, is now located at 1700 Queens

Road in the Myers Park

neighborhood of Charlotte.

Dr. Fox and his associates, not satisfied with just enhancing Charlotte's economic status, also wanted to make the town an important cultural place. A group headed by Fox provided the impetus for establishing the North Carolina Military Institute . "Those gentlemen who originated and pushed forward the scheme are entitled to much credit for energy and zeal," proclaimed the Western Democrat . Fox and his friends raised $15,000 by selling stock to individuals and received $10,000 from the City of Charlotte, also to purchase stock. The voters of Charlotte had approved this financial outlay in a special referendum held on March 27, 1858. Dr. Fox and his fellow boosters bought a tract of land about one-half mile south of Charlotte beside the tracks of the Charlotte and South Carolina Railroad and hired Sydney Reading , a contractor, to oversee the construction of Steward's Hall , a massive, castle-like, three and four-story brick edifice designed to look like the buildings at West Point.

The superintendent of the North Carolina

Military Institute

was Daniel Harvey Hill

. "As a teacher I have

never seen his superior," one of his students exclaimed. "He had

the rare capacity of interesting his pupils and of compelling them to use

their faculties, often it seems unconsciously, in a manner that surprised

themselves." "In clearness of interpretation, in relevant and

apposite illustration, he has never been excelled," proclaimed Henry

E. Shepherd

, another student

of Hill's at the North Carolina Military Institute. D. H. Hill's influence over the educational philosophy of the North Carolina Military Institute was paramount. In keeping with his gloomy appraisal of human nature, Hill insisted that discipline must be rigorously enforced. Just as at Davidson College , he held firmly to the belief that young men, unless closely supervised, would inevitably go astray. "The great sin of the age," he told the Education Committee of the North Carolina Legislature in January, 1861, "is resistance to established authority." Cadets had to attend chapel twice daily -- in the morning to listen to a sermon and in the afternoon to hear Biblical instruction -- as well as go to church on Sunday. Henry Shepherd remembered Superintendent Hill's lectures in the chapel with fondness. "I listened eagerly to the comments of the 'Major' as he read the Scriptures in chapel and at times revealed their infinite stylistic power," he wrote many years later. |